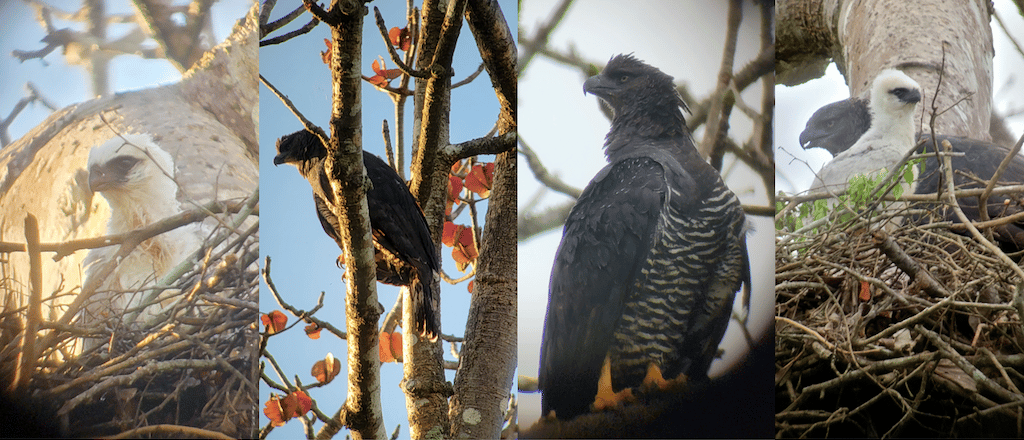

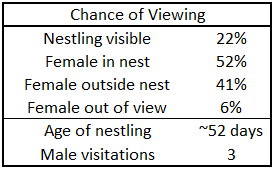

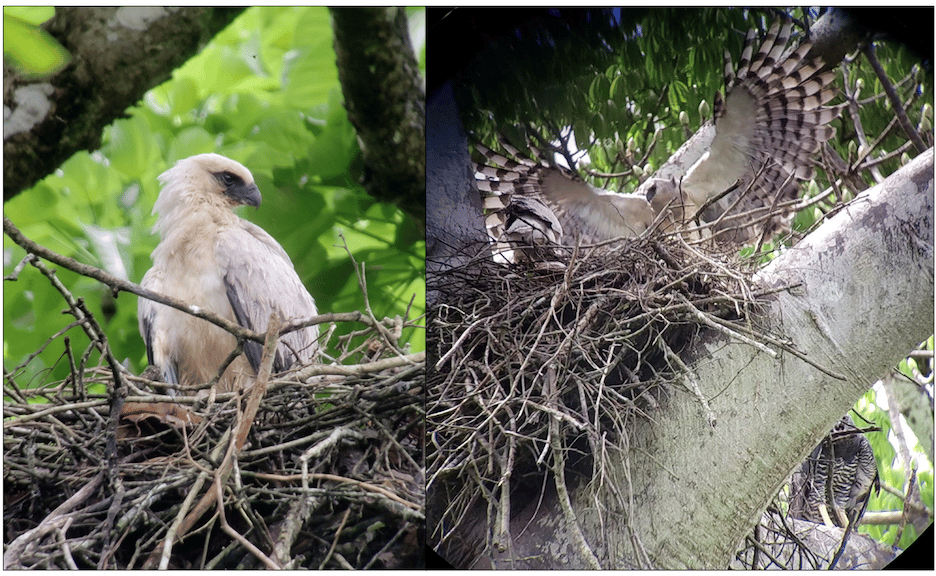

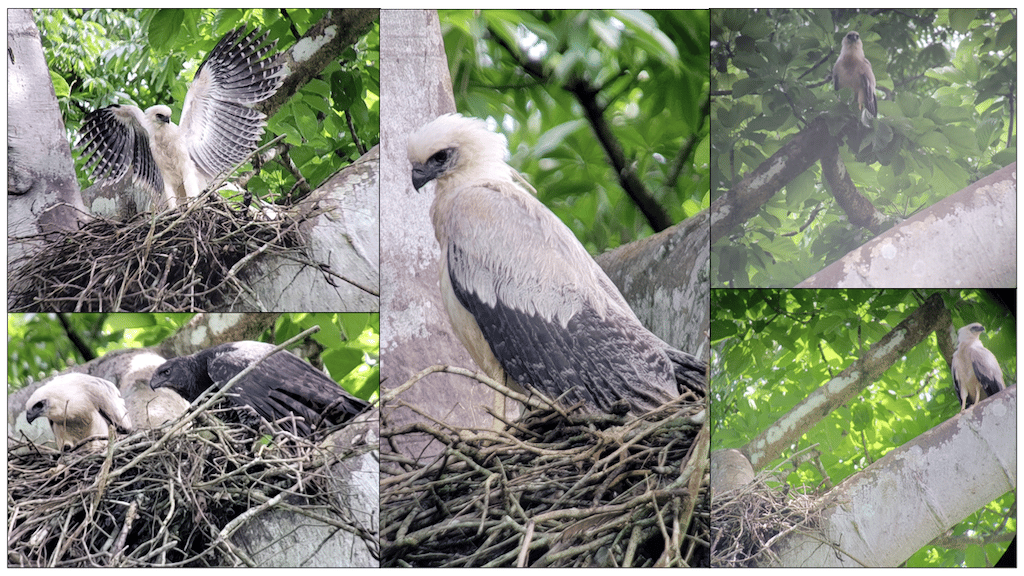

Nestling and dark-morph Crested Eagle (Morphnus guianensis) female.

By Alexandra Eastman

Little is known about the behavior of the Crested Eagle. Although it is one of the largest eagles in the Americas, it is also one of the most difficult to see. Its scientific name, Morphnus guianensis, has the Spanish word for guide (“guía”) right in the name, indicative of the need for one if you ever aspire to add this magnificent raptor to your life list! Moyo Rodríguez, one of the many talented guides employed at Canopy Camp—a world-renowned birder’s mecca located in the Darién province of Panama—discovered an active nest of a pair of these rare birds in the early part of 2022 nearby the Canopy Camp. Moyo regularly spotted two adult eagles along El Salto Road, an area rich in wildlife, and surmised there might be a nest in the area. He searched the densely vegetated secondary growth rainforest for five days. Finally, on January 9th, his persistence paid off when he came upon an emergent Cuipo tree (Cavanillesia platanifolia) with the beginnings of a nest in its first fork, about 22 meters above the ground. More exciting was the sight of two adult Crested Eagles perched in its branches. The male, a light-morph bird, held a freshly killed Red-tailed Squirrel in his talons, while the larger female, a rare dark-morph individual, perched nearby.

Left to right: Nest with female further up the branch; Male with Red-tailed Squirrel. Photos by Moyo Rodríguez.

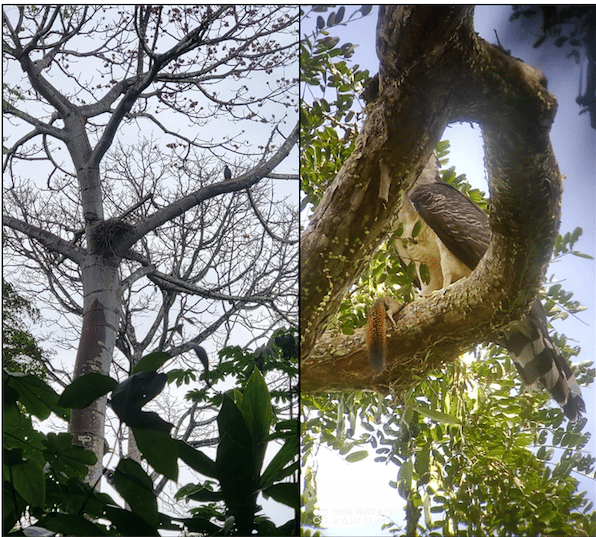

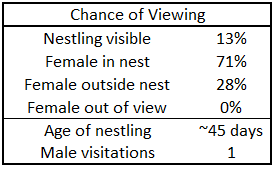

Many who come to the Canopy Camp will ride horses and travel by canoe for a chance to glimpse the much-sought-after Harpy Eagle. While a rare find, Harpy nests can sometimes be located by following the sounds of the eagles’ vocalizations. Crested Eagles, however, are comparatively silent, making it even more difficult to locate and study them. What made this nest even more of a rarity was its relative accessibility. One only had to take a 20-minute car ride followed by a 20-minute hike to a location that could provide visitors with an excellent vantage point of the nest. The Canopy Family team recognized the unique research potential to make consistent, detailed nest observations of this rarely studied bird, and a data collection plan was quickly organized. The nest was to be watched 6 hours a day, 6 days a week until the time of fledging (when the chick would take its first flight). One biologist would be conducting the observations while always accompanied by a staff member of the Canopy Camp. A shelter was constructed as quickly and covertly as possible to minimize disturbance to the nest. Trails on either side of the shelter allowed observers to walk 180 degrees around the nest tree, keeping a safe distance, to view the surrounding trees that the female might perch in to keep a close eye on her nestling. On April 18th, when the eaglet was judged to be around 45 days old, nest observation was initiated and would continue until fledging at around 110 days. It would be the beginning of 9 weeks of observation and over 300 hours spent in the field documenting the daily life of these mysterious eagles. Below, you will find a report of some of these amazing weekly observations.

Left to right: View of the nest from the observation shelter; Taking observation notes beneath the shelter of a mosquito net; Signs put in place around the site to ensure no one disturbed the nesting/observation process.

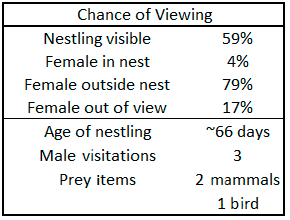

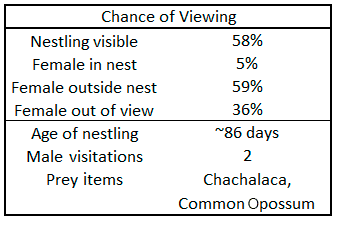

Week 1 (April 19 – 25, 2022)

Prior to the official start of observations, the only signs of the nestling’s existence were movement behind the nest’s loosely arranged sticks and a hint of white fluff occasionally cresting the rim of the nest. During the first week we would see the nestling in brief time segments of a few minutes each when it stood up to look around before disappearing behind the branches. On only a few occasions, we saw its small white wings stretching and beating the air awkwardly. The sight of emerging wing feathers and the amount of time the chick was able to stand together confirmed its age to be about 45 days old.

The mother spent the majority of the day on the nest during this time period. At times she would move to a nearby branch to sun herself after sheltering her chick from a drenching tropical rainstorm. Another task that necessitated leaving the nest was to collect branches to maintain the nest structure, without which it could quickly degrade from the unrelenting humidity and heat of the rainforest conditions. Collecting branches serves another beneficial function related to combating biting insects, fungus, and pathogens which can impact the health of the young. Studies have shown that this behavior of adding new leaves and branches to the nest reduces these assailants which can quickly build up in a stationary nest. The male, the main food provider, was finally seen at the end of this week delivering an unknown food item to the nest. His arrival was sudden and proved a challenge to capture.

Week 2 (April 26 – May 2, 2022)

While the female began spending more time perched either in the branches of the nest tree itself or in trees immediately next to it, every midday she was consistently observed in the nest brooding over the chick. The dry season was ending, and the wet season was beginning. The Cuipo tree in which she was nesting had dropped its leaves during the dry season, and its large papery pinkish flowers from the first week of observation had been replaced with the beginnings of leaf buds that did nothing to shelter her or the chick from the harsh rays of the equatorial sun. Since birds do not sweat, they only have a few options by which to lower their body temperature. Her open mouth and occasional gular fluttering (an action in birds similar to panting) were signs that her body was showing some level of heat stress, but her vigil over the nest was necessary to shield her chick from these harsh environmental factors.

Left to right: Female on a branch in the nest tree; Nestling keeping its mouth open to thermoregulate; Female perched in a tree nearby the nest.

Week 3 (May 3 – 9, 2022)

At the beginning of the eaglet’s development, the male had the difficult task of providing nourishment for three birds—himself, his mate, and their young. He excelled at this job as he delivered prey items an average of three times a week during our observation periods. It can be assumed that he was bringing food possibly six times a week since we were not present around the clock.

The male had a routine that began with flying to the nest, staying momentarily to leave his prize, then moving to a nearby branch and joining the female in calling. They would spend around two to three minutes calling back and forth to each other, their wings pumping out from their sides with every sound. After a few minutes of vocalizations, the male would fly off to an unknown destination, and the female would immediately cease calling. The chick would be begging from the nest with sharp, short cheeps, and the female would fly to the nest soon after to remove the prey item’s fur or feathers and begin to feed the chick and herself.

On Sunday, May 8th, Mother’s Day in the United States, the male came to the nest for the first time without prey. What followed was a behavior we had never seen before. Instead of staying for a mere three minutes, the male stayed for almost 30 minutes. During this period, he attempted to approach the female multiple times, only to be charged at by the seemingly annoyed and much larger bird, which caused the male to retreat to another branch but not to give up his unknown intentions. As the two birds called back and forth, the male continually approached the female, hopping and flying from branch to branch as she charged, hopped, and flew around the branches in an awkward dance within the nest tree. The male flew off and we thought the strange encounter was over, until less than two seconds later when he flew to the nest with a branch, something we had only ever seen the female do. He then continued his previous efforts of approaching the female and being chased away until finally he flew off unceremoniously, leaving us at a loss for an explanation of this strange but exciting event.

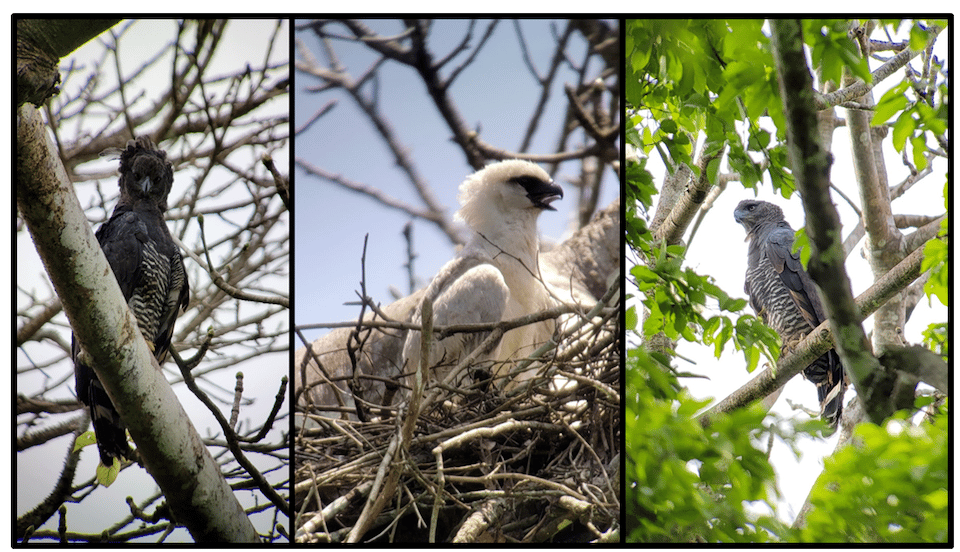

Left to right: Male in nest tree after delivering prey; Nestling; Female perched in tree close to the observation site.

Week 4 (May 10 – 16, 2022)

Interactions between the eagles and other species were also something we were looking out for during our observations. Since the first week of observation, White-headed Wrens were consistently seen flying to and from the bottom of the nest to disappear inside the tangle of its branches. Other birds seemed unperturbed by the eagles’ presence as well, and we would frequently see Red-lored Parrots, Squirrel Cuckoos, Masked Tityras, Blue-and-yellow Macaws, and one brave Dusky-capped Flycatcher calling in the branches only inches from the face of the young eagle.

There were some encounters that were not so passive, mostly a result of Turkey Vultures coming too close. Whenever these birds circled low, the female would follow them with her gaze, feathers erect, emitting a long shrill call. Two other instances of birds reacting to the eagles’ presence were a Black-chested Jay seen dive-bombing the female as she attempted to collect nest material in an adjacent tree, and Keel-billed Toucans who would call excitedly when the female would perch close to their own nest tree.

After the 3rd week, the female would only return to the nest when placing branches or feeding the chick, as by this stage in the eaglet’s development it was better able to self-thermoregulate. One day during this week we could not locate her in the surrounding trees. We were drawn to commotion from toucans in the trees to the north of the nest. We followed the calls with the notion that they might indicate the female’s location. Sure enough, the calls led us right to her deep in vegetation, with the distressed toucan parents hopping around in the branches around her and calling relentlessly.

Left to right: Female in tree near the Keel-billed Toucan nest; Nestling; (top) Female leaving the nest after feeding; (bottom) Female feeding the chick.

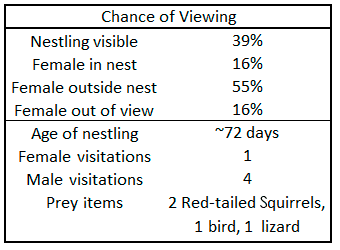

Week 5 (May 17 – 22, 2022)

This week brought many observational firsts. As we arrived one morning around noon, we saw the female carrying a lizard to the nest. This was the first time we had seen her contribute to the hunting effort. The same day marked a milestone in the chick’s development as it was observed attempting to feed itself (although unsuccessfully). Later in the week the eaglet practiced its own hunting skills by continually pouncing and pulling on sticks within the nest. While these first attempts were very awkward, with much falling over and wing flapping to balance, it was the start of honing skills that would someday result in the keen stealth and ability of its parents.

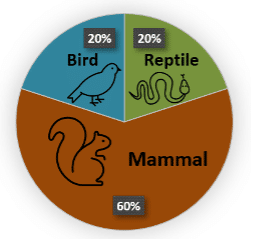

Another first was the species-level identification of a prey item brought by the male. Up until this point we had never been in the right position or angle to see which species of prey the male delivered. We could identify each as a mammal, bird, or reptile but never which specific species. The cup of the nest was deep enough so that once the male landed, whatever he was carrying was out of our sight. This week we were lucky with our timing and had the camera set to slow motion in time to record the male flying from an angle with full visibility of what he was carrying: a Red-tailed Squirrel.

Left to right: Nestling; Male delivering prey with the female below calling.

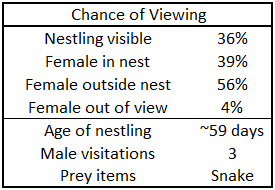

Week 6 (May 23 – 29, 2022)

At this point the female started to spend more time away from the nest and out of view of our observation site. It was difficult to determine if she was remaining in the vicinity of the nest, as her favorite perches would move further and further away by the day. At the same time, the green season lived up to its name, and vegetation increasingly obstructed the viewability of the area. One piece of evidence indicating that she was in fact straying completely out of view of the observation area was an instance when she had not been seen for multiple time blocks and we realized the commotion of toucans we had been hearing further down the trail could be giving away her location again. Sure enough, she was about a 5-minute walk down the trail, perched in some trees with the toucans calling around her. This confirmed that she was straying further from the nest tree she had consistently stayed close to for the first few weeks.

Another sign that she was in fact a good distance from the nest and not just obscured by leaves was when the male delivered a Red-tailed Squirrel and for the first time was alone in his vocalizations, which were more infrequent without a companion to reply to. The chick, confronted with a prey item in the nest but no mom to feed it, spent some time manipulating the carcass itself before we finally saw it successfully take its first bites of meat. The eaglet was also beginning to take advantage of more time spent alone to practice some flying skills. It would flap its wings vigorously in bouts, awkwardly hop-flying from side to side of the nest and even hovering momentarily above the nest. While this looked promising for a first flight, we knew we had a few more weeks before the eaglet would be ready to exit the nest for the first time.

One day when the female was out of view, we heard the signature call that normally preceded the arrival of the male with food and then a second call of a Plumbeous Kite which had been seen in previous days soaring high over the nest tree, never low enough to elicit a defensive reaction from the eagles, as we had witnessed in response to vultures. The female burst from the canopy above us, flying directly to the nest. The male followed closely after her, dropping a Central American Opossum into the nest. Less than a second after his arrival, we were surprised to see the kite in close pursuit, diving where the opossum had been dangling from the male’s talons just moments before, circling back, and then careening off into the canopy and out of sight. The female and male both faced the direction where the kite had disappeared for a few minutes, before the male flew off and the female began to feed the chick the almost stolen prize.

Left to right: Nestling; Female; (top) Male’s arrival; (bottom) Female in the nest after the male, seen on the branch behind, delivered a prey item.

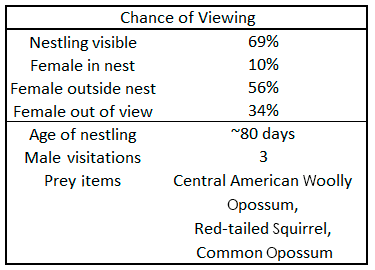

Week 7 (May 30 – June 5, 2022)

This week marked the first time an entire 6-hour block passed without a single observation of the female. Every time we glimpsed her was a moment treasured as we realized the possibility of its being the last time we would witness behaviors that we had become accustomed to seeing on a regular basis.

There had been a few times that helicopters flew around the skies above the nest. These helicopters were never commercial flights, instead they were SENAFRONT, the Panamanian National Border Service. The male at one time even delivered a meal despite the loud noise and movement above him. Neither the chick nor the adults had noticeably reacted until this week when the chick was alone in the nest and a helicopter flew over the nest tree. The chick reacted in a similar fashion to the female when soaring vultures would venture too close. It raised its feathers and opened its wings slightly to its side, emitting a warning cry similar to those we had heard from the female in the past. As the helicopter grew more distant, the chick visibly relaxed, even pulling a leg up to perch on the nest edge.

Left to right: Nestling reacting to a helicopter; Nestling after a rainstorm; Nestling flapping its wings.

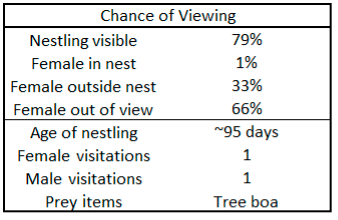

Week 8 (June 7 – 14, 2022)

The young eaglet’s flying practice intensified during this week, and every time it ventured to the rim of the nest to look over the edge or started hovering in the air, we held our breaths and hit record on the camera. The final day this week, for the first time, we saw the chick about half a meter outside of the nest, sitting on the branch immediately underneath. The remainder of the day the eaglet would make short hop-flights to and from this spot on the branch. Usually hunched over and holding its wings loosely at its sides, the chick would stand carefully for a few minutes at a time before retreating to the nest with a short hop or some tentative steps. We knew the moment we had been waiting for all these weeks would soon arrive.

It was increasingly rare to see the female eagle, and we had yet to see evidence of her hunting efforts except for the one instance in the beginning of Week 5. This also meant that the guests visiting the Canopy Camp, sometimes specifically to see a Crested Eagle, would need more patience and luck than in previous weeks to see an adult bird.

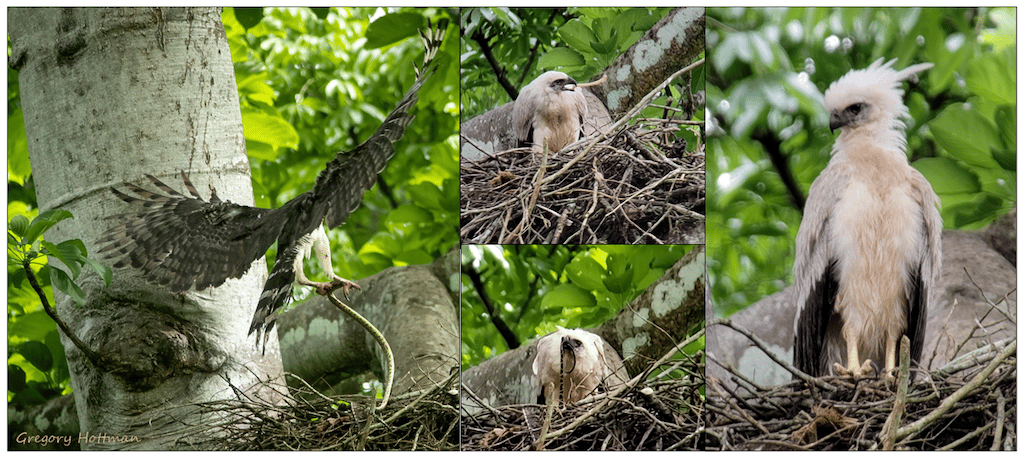

Of all the days to visit the site during this week, the group of guests who visited on this occasion chose the right one. Not only did the male deliver prey—which was itself extremely lucky to observe given that on average the male was only present for 3 minutes out of every 12 hours we were there—but the female delivered her own prey item not long afterwards. We have one of these guests to thank for an amazing photo of the prey item the male brought, which allowed us to identify it to species: Corallus ruschenbergerii, a species of tree boa.

Left to right: Male bringing a tree boa (Corallus ruschenbergerii) to the nest (photo by Gregory Hoffman); (top) Chick handling bones from past prey items; (bottom) Chick holding the tail of the delivered tree boa in its beak; Nestling.

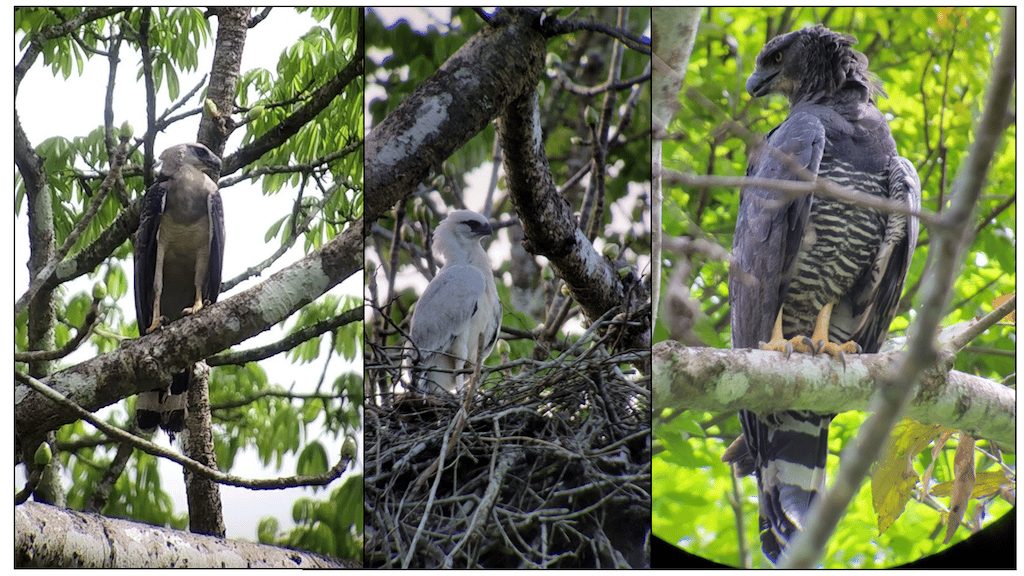

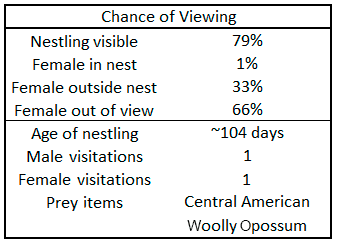

Week 9 (June 15 – 22, 2022)

Every day we kept our eyes glued to the nest as the chick teased us by continually flying from rim to rim, hovering almost a meter above for a few brief wing pumps, and hopping in and out to the branch just outside the nest. However, at this point it had yet to make a real attempt at flying. The female was gone for nearly three quarters of the time we were present, but the chick was more visible than ever and was constantly testing the limits of its abilities. Each day the eaglet would walk and hop further and further up the branch, using its wings for stabilization but always returning to the nest without resorting to actual flight.

When it finally happened, the chick was very far out on the branch (about 10 meters from the nest) and was hopping around the leafy branches so much that it was slightly difficult to keep track of it. The back-and-forth head movements that raptors use to gauge depth were clues we had learned to look for in the female in advance of her flights. This was it: the chick was going to try to fly! Minutes went by before the eaglet pushed itself away from the branch and finally flew to a branch behind the nest—about 9 meters into the empty air between the two perches. It landed, and we celebrated with hushed, excited squeals.

Left to right: (top) Nestling before hovering above the nest practicing for flight; (bottom) Mother and nestling in the nest after feeding; Nestling; (top) Eaglet sitting on a branch behind the nest after taking its first flight; (bottom) First time the chick was seen outside the nest.

Identified Prey Items:

The eaglet’s first flight symbolized the final chapter of an opportunity made possible through the excellent teamwork of the Canopy Family and was enhanced by the input of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, The Peregrine Fund, and Dr. Charles Munn.